SAH Triumph TR4

A HOT ONE BY HURRELL!

Sports Car July 2s 1962

JOHN BLUNSDEN tries Neil Dangerfield’s Triumph TR4 on road and circuit, and finds that Sid Hurrell’s modifications make it a thoroughly tractable 130 mph two-seater – a weekday shopping car and a weekend race winner.

In these days of sprint-tuned production engines and lightweight racing trailers, it is a change to find a car that serves as a town hack from Mondays to Fridays, and then, with little more than a service and a ‚paraffin overhaul‘, wins a motor race at the weekend. The well-known white Triumph TR4 owned and driven by Neil Dangerfield, and prepared and maintained by Sid Hurrell, is such a car. Tractable enough to trickle along with only 800 rpm showing on the rev counter, yet with sufficient power to reach a road speed of 130 mph in overdrive top with the aid of a clear motorway.

Sid Hurrell with SAH 137 – Neil Dangerfield’s racing TR4, which is prepared and maintained by S.A.H. Accessories, at Leighton Buzzard.

FAMILIAR NUMBER

Its registration number SAH 137 has been a familiar sight on British circuits for several years, and it has always been associated with a more than averagely successful car. Sid Hurrell used to carry it when he was racing his own TRs, and Neil Dangerfield has inherited it for what is – from a mechanical standpoint – virtually a Hurrell works entry.

As such it acts as a guinea pig for new items of performance equipment, and in one or two respects it is a little different from the normal run of Hurrell-modified TRs. The compression ratio, for example, is approximately 10.2 to 1 instead of the 9.5 to 1 of the ‚production‘ modified engine. But as Hurrell makes a point of offering nearly all his performance equipment as separate items, as well as in a ‚package deal‘, a TR owner can have his car modified to virtually any specification.

The conversion of the Hurrell-Dangerfield car can be divided into three parts – the engine, the suspension, and the bodywork. The engine is boosted in power from 105 to 135 horsepower, and a stronger clutch and an oil cooler are fitted. The suspension is modified at both ends for competition use, and work on this is continuing in an effort to improve the handling. The use of glass-fibre panels for the unstressed body parts has helped toward the total saving in weight of some 124 pounds. Dangerfield, therefore, is able to take full advantage of the 5 per cent reduction in catalogue weight allowed at scrutineering.

CONVENTIONAL CONVERSION

The Triumph TR engine is a tough unit, and Hurrell has found it unnecessary to resort to highly elaborate and costly modifications in order to achieve the required power. In fact, the conversion is fairly conventional, although a lot of

care is taken over the detail work, and this no doubt contributes considerably to thesuccesses earned by the modified engine.

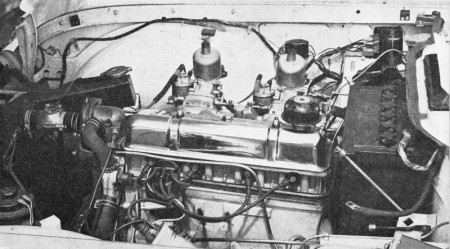

Apart from the raised compression ratio, the cylinder head has reshaped and highly polished combustion chambers and ports, the latter being matched to polished ports of the inlet manifold. Hurrell strongly recommends SU carburettors with the ‚hot‘ TR engine, as they appear to give a more progressive power curve and better fuel consumption than alternative set-ups. The twin H6s have special needles, giving a fairly rich setting, but otherwise they are unchanged. No air filters are fitted on Dangerfield’s car, and despite this induction roar is modest.

The SAH four-branch extractor-type exhaust manifold has proved a great success, and this item is now being offered as a factory extra by Standard-Triumph, and should soon be homologated. Triumph testers have found that it offers a useful bonus of eight horsepower over the standard manifold. The four branches blend into twin parallel pipes, which in turn are joined into a single outlet ahead of the 18-inch Servais straight-through silencer.

VALVE TIMING

Although standard-size valves, are used, they are fitted with competition springs, and are operated from a camshaft giving a higher lift, but not being so ‚hot‘ that low-speed torque is sacrificed noticeably. The modified cams open the inlet valves 23 degrees before TDC, and close them 64 degrees after BDC, while the exhaust valves open 64 degrees before BDC, and close 23 degrees after TDC. This timing compares with 15, 55, 55, and 15 degrees, respectively, from the standard camshaft, while the valve lift is increased to .428 inch, with a clearance of .018 inch.

Sid Hurrell strongly recommends the converted engine in 2,138 cc form, as on the 1,991 cc unit the lack of torque at the bottom end is more noticeable. The Dangerfield car, of course, has the larger-capacity liners, and this conveniently moves it out of a class often dominated by ‚hot‘ Bristol engines in ACs, and TR units in lightweight Morgans!

The engine is fully balanced, with a lightened flywheel and special Glacier bearings, and the standard Borg and Beck clutch is fitted with a Mintex competition centre plate. The oil cooler kit incorporates a modified full-flow filter, and the engine is cooled by a Kenlowe electrically operated and thermostatically controlled fan.

HIGH-GEARED

Production TR4s have a 3.7 to 1 axle, or a lower 4.1 to 1 ratio if the optional Laycock de Normanville overdrive is fitted. When Danger-field wanted his TR4 no overdrive cars were available, so he took a normal model, with the 3.7 axle, and Hurrell subsequently fitted the overdrive without altering the axle. The result is a highly geared car, offering really effortless high-speed cruising, and a useful top speed on the faster circuits. Instead of the flick switch extending from the steering column, the overdrive is operated from a tumbler-type switch fixed to the right-hand steering wheel spoke. Apart from this, the Smiths racing rev counter, which replaces the production type, and the glass-fibre racing seat – fully padded and trimmed in black vynide to match the rest of the upholstery – the cockpit looks just like that of any other TR4, although a growing collection of ‚Passed by Scrutineer‘ labels hanging from the facia discloses its competition history.

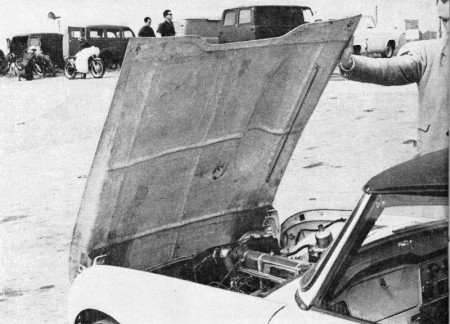

Unlike the Hurrell glass-fibre body panels for the TR2 and TR3, the conversion for the TR4 follows the same profile as on the standard model. Outwardly, therefore, the racing TR4 looks little different apart from the lack of bumper bars.

A close inspection, however, reveals a plastic front section, saving 25 pounds in weight, front wings (9 pounds less each), rear wings (6 1/2 pounds less each), and boot lid (15 pounds lighter).

Special 60-spoke centre-lock racing wheels are fitted, and the suspension modifications when the car was tested included stiffer front springs, Variflo adjustable dampers all round, and a f inch anti-roll bar at the front. Even with the

dampers on their softest settings the car was tailored for fast motoring, a harsh ride being offered at low speeds. At the same time, when the car was put on a circuit (Brands Hatch) it revealed too much under-steer, and a considerable

effort was necessary to prevent it running out of road on left-hand bends.

The Dunlop RS5 tyres were tried at 32 pounds front, 37 pounds rear at first, as recommended, but subsequent adjustment to a more balanced pressure between front and rear seemed to offer a small improvement in handling. However, before the car’s potential performance could be used to the full, a considerable improvement in handling would be desirable. Dangerfield has spun off several times in his efforts to kill the understeer, and subsequently has not been driving ‚ten-tenths‘. With the handling sorted, therefore, he should really go!

SUSPENSION MODS

It is difficult to pinpoint the trouble, but a thinner front anti-roll bar, softer springs and firmer damper settings might be a worthwhile line of experiment. This handling problem highlights the difficulty of tailoring a car satisfactorily for road use and for racing, and indicates the difference between fast road driving and actual racing. Normally, of course, racing tyres are fitted for track use, and since the car was tested a modified front wheel set-up has been tried, giving a castor angle of 3 degrees. It is likely, therefore, that Danger-field’s car will be handling well by the time these words are read.

A highly polished rocker cover sets off the Hurrell-modified 2,138 cc TR4 engine, which has an output of 135 horsepower. Hurrell is a great believer in SU carburettors for the Triumph engine, and these are mounted without air cleaners. A Kenlowe thermostatically controlled electric fan looks after the cooling.

The Hurrell engine conversion has been an unqualified success in that it has turned the TR4 into a competitive racing model without reducing its docility as city transport. The engine is remarkably flexible at low speed, so that the

resonant exhaust period between 2,500 rpm and 3,000 rpm is no mbarrassment when motoring in built-up areas, the mph per 1,000 rpm figure being in excess of 24 for overdrive top.

There is no carburation lumpiness at low speed, and the unit will tick over indefinitely, even though throughout the period of the test the choke was not used once. Obviously the mixture (100 octane fuel) was on the rich side, so that

the all-in figure of between 20 and 21 mpg was very reasonable. The only suspicion of plug-wetting occurred when the accelerator was opened wide after a long session at low speed; then there were a few seconds of unevenness as the revs built up.

The Hurrell-Dangerfield TR4 is some 124 pounds lighter than standard, partly due to the use of glass-fibre body panels. This lightweight bonnet section is secured by two Dzus fasteners to the scuttle.

6,000 RPM ON TAP

Further up the scale, there is a second resonant period beyond the 4,000 rpm mark as the engine gets into full song, and at first it seems that peak revs are about 5,500 rpm. There is a slight rough patch at this point, but if the acceleration is sustained it evens out again at 5,700 rpm, and the engine goes on crisply to 6,000 rpm without any indication of being overstressed.

Normally, of course, it is not necessary to use these revs, and Dangerfield usually comes in after a race with the tell-tale somewhere near the 5,500 rpm mark – unless he has been in a dog-fight? For maximum acceleration a change-up

is called for at about 5,000 rpm. Sustained high engine speed failed to drop the oil pressure and water temperature readings from their normal positions, and only once was there any running-on after the ignition was cut.

The car cruised happily at 4,500 rpm in overdrive top – 110 mph – and a best reading of 5,300 was obtained with the aid of a run-up of several miles on Ml, corresponding to 130 mph. Using 5,000 rpm in the gears, the maximum speeds

available in each ratio are: 1st, 31 mph; 2nd, 50 mph; 3rd, 76 mph; o’drive 3rd, 93 mph; top, 100 mph. Naturally, these speeds can be improved by ten per cent if the revs are allowed up to 5,500 rpm, and by 20 per cent if the occasion demands the use of 6,000 rpm. No maximum speed has been given for overdrive second because the unit would not take full engine power; in any case, this ratio would not be used during normal motoring.

The car’s soft top withstood top speed well, and of course with the facia air vents it is possible to drive the car with the side windows up. Above 100 mph there was some wind buffetting around the front of the car, the air seeming to swirl around the headlamp shields and cause the plastic body panel to vibrate. Although it is quite a noisy car at high speed, the TR4 is very stable, and when an unexpected large ‚bump‘ was hit at between 110 and 115 mph, it took off momentarily, and landed squarely, without a lot of drama.

The brakes were up to the extra engine performance, the only deficiency being an occasional lagging of the left front pads behind the right front pair, resulting in an initial pull to the right on a light application. The brakes smelt ‚hot‘ after continual pounding, but did not lose their power. The clutch transmitted the power satisfactorily, although the pedal was adjusted to the point of slip, and had to be operated accordingly.

The rush of air through the facia grilles balloons the soft top as the TR4 is lined up for Paddock Bend at Brands Hatch, both the door windows being closed. The track test exposed considerable inherent understeer, which is being corrected by further suspension modifications.

One of the big attractions of this car is that, although it has an impressive performance and is well able to see oft many a more ‚rorty‘ sports car, it also has the docility of a family saloon, and can be driven in a similar manner. The vivid acceleration and the healthy exhaust crackle can be saved for when it is really needed, and when this happens these are the figures which are likely to be obtained:

- 0 to 30 mph – 3.0 seconds

- 0 to 40 mph – 4.8 seconds

- 0 to 50 mph – 6.6 seconds

- 0 to 60 mph – 8.6 seconds

- 0 to 70 mph – 11.2 seconds

- 0 to 80 mph – 14.0 seconds

- 0 to 90 mph – 17.6 seconds

- 0 to 100 mph – 22.8 seconds

Approximate cost of the extra performance; £120 for the engine conversion; £68 for the body parts; £22 for the suspension conversion; and £70 for the racing wheels.

»» The original article you will find here.

Filed under: History, Information, Mobilia, Optimierung - improvement | Closed

Schlagwörter: Neil Dangerfield, S.A.H., sah, Sid Hurrell, tr4, triumph tr4

Du muss angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar zu veröffentlichen.